The Definitive Guide to Power in Organization: 10 Sources, 9 Tactics, and Ethical Use

Published: 06/10/2025

Many people believe that power in an organization is solely tied to titles or positions. You may have assumed that power is reserved for the CEO, the department head, or the senior manager—those with the prestigious job titles. But this belief is limiting. The reality is that power is not just a byproduct of a title. It is dynamic, accessible, and, quite often, misunderstood. Power can be wielded by anyone within an organization, regardless of rank, and can be built through various sources and influence tactics.

In this definitive guide, we will go beyond the usual theories and explore the deeper complexities of power in organizations. You’ll discover 10 Sources of Power, the foundational Resource Dependency Theory (RDT), and 9 Influence Tactics that you can start applying immediately. Most importantly, we’ll also provide an Ethical Framework to ensure that your mastery of power is both effective and responsible. Whether you’re at the top or starting from the ground up, understanding and leveraging power can significantly enhance your influence and impact within your organization.

Defining Organizational Power and Influence

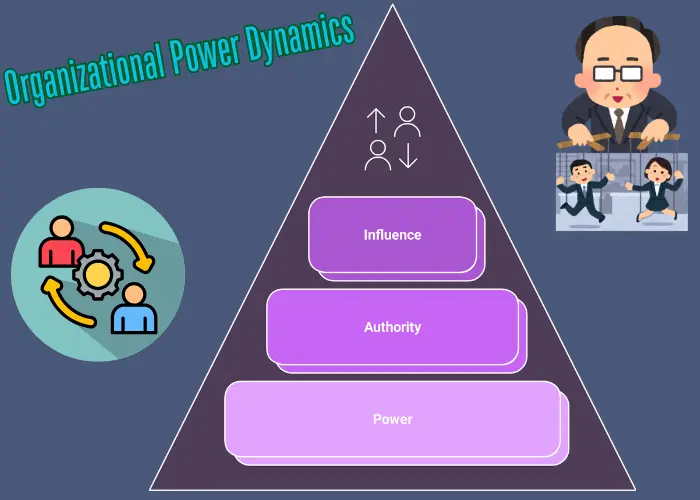

Understanding power in an organization starts with distinguishing between power, authority, and influence. While these terms are often used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings in the context of organizational behavior:

- Power is the ability to affect others’ behaviors, decisions, or actions. It’s often rooted in control over valuable resources.

- Authority is the formal, institutionalized right to make decisions and issue commands, typically granted by position or rank in the organizational hierarchy.

- Influence, on the other hand, refers to the subtle, often informal ability to sway others’ thoughts, decisions, or behaviors, regardless of position or authority.

This distinction is crucial because power in organizations is not always tied to a title or authority—it can be derived from various sources that provide access to critical resources and influence.

The Core Principle: Dependency = Power

At the heart of understanding organizational power lies a fundamental principle: Dependency = Power. Simply put, power is rooted in the control over resources others value and need.

If someone has access to a resource that is crucial for others’ success—be it knowledge, a key decision-making role, or critical tools—they gain power over those who depend on that resource. This dependency establishes a relationship where the more valuable and irreplaceable the resource, the greater the power the person controlling it holds.

This core principle explains why power is not just about titles. It’s about access and control over what others find essential to achieve their goals.

Power is not given. It’s taken — by those who understand where value truly lies.Jeffrey Pfeffer, Professor of Organizational Behavior, Stanford Graduate School of Business

Resource Dependency Theory (RDT): The Three Pillars of Control

Resource Dependency Theory (RDT) offers a clear framework for understanding the dynamics of power in organizations. According to RDT, power is derived from the control over resources that others depend on. The theory highlights three key pillars that make a resource valuable enough to grant power:

Importance:

- The resource must be critical to the success of the dependent party. This could be a specific budget allocation, a unique piece of technology, or proprietary information. For instance, a senior finance officer who controls funding for key projects has significant power because their approval is required for the success of other departments.

Scarcity:

- The resource must be scarce or difficult to obtain. If a resource is readily available, it doesn’t hold as much power. Consider a critical legacy system that only one employee knows how to operate. That employee holds significant power because they are the sole gatekeeper to that resource, and no one else can perform the job without them.

Non-Substitutability:

- The resource must have no viable alternatives. If a resource can be easily replaced by another, the power associated with it diminishes. For example, a manager who controls the only project management software that the team relies on has greater power compared to a manager with an easily replaceable tool. The lack of a substitute ensures their influence remains intact.

Imagine a small, mid-level IT employee who works in a large company. This employee is not high on the organizational ladder, yet they hold a significant amount of power. Why? Because they are the only person who knows how to operate an ancient, critical legacy system that powers the company’s financial reporting. Without this employee’s expertise, the entire department would grind to a halt.

Despite having a lower title and few formal powers, this individual wields scarcity power—they control a unique, irreplaceable resource. This example illustrates how power can exist at all levels of an organization, even outside of formal authority or seniority.

The 10 Sources of Power: A Complete Organizational Framework

Power in an organization doesn’t come from just one source. It’s multifaceted, and understanding the different types of power is crucial to leveraging it effectively. In this section, we’ll explore the 10 Sources of Power, breaking them into three distinct categories: Positional Power, Personal Power, and Structural Power. Each type of power offers a unique path to influence within the organization, whether it’s based on your role, your expertise, or your strategic position within the network.

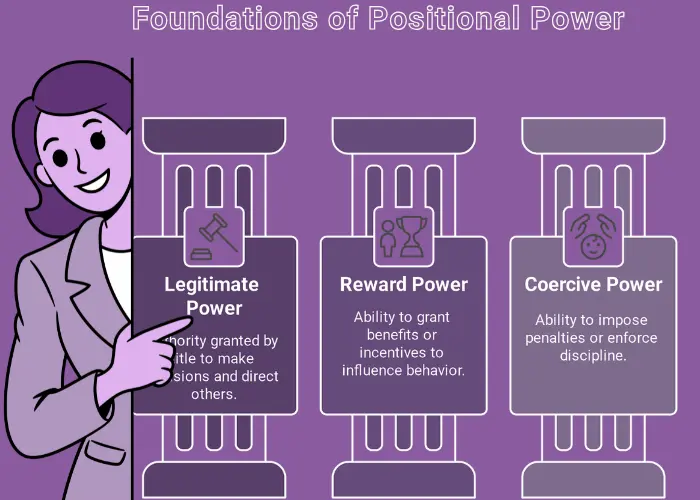

Positional Power (Bestowed): The Power of Title

Positional power is granted to individuals based on their formal role or title in the organization. This type of power comes from the authority and responsibility vested in a particular position. Let’s break down the three main types of positional power:

Legitimate Power:

- This is the power that comes with a title or position. It’s the authority granted by the organization to make decisions and direct others. For example, a manager has legitimate power because they have been formally given the right to oversee a team’s operations.

Reward Power:

- The ability to grant benefits or rewards to others is another form of positional power. This can include promotions, raises, time off, or special perks. Diversifying rewards—offering different types of incentives, like recognition or professional growth opportunities—can strengthen this power. A manager who has the authority to provide rewards can influence their team’s behavior by aligning rewards with desired outcomes.

Coercive Power:

- This is the ability to impose penalties or punish others. Coercive power is often less effective when used excessively, but in situations requiring discipline or correction, it becomes necessary. For instance, a supervisor might have coercive power if they can enforce consequences for poor performance or misconduct.

Personal Power (Earned): The Power of You

Personal power is earned through one’s expertise, relationships, and reputation within the organization. Unlike positional power, it’s not about your job title—it’s about what you bring to the table on a personal level. The three types of personal power are:

Expert Power:

- This power stems from specialized knowledge or skills that others need. It’s the go-to knowledge in a specific area that others depend on. For example, a software engineer with a deep understanding of a unique coding language or a legal expert who holds valuable knowledge about compliance laws. The more unique and crucial the expertise, the greater the expert power.

Referent Power:

- Referent power is the influence you have because others admire or respect you. This type of power is based on trust, likeability, and personal relationships. Leaders who have high referent power tend to build strong, loyal followings because they have developed a reputation for being trustworthy and charismatic. Think of the manager who, because of their integrity and empathy, has employees who genuinely want to follow them and work toward their shared goals.

Informational Power:

- Control over access to critical information also provides power. However, in this case, it’s not about hoarding information—it’s about genuinely sharing it when it’s needed. For example, a team member who is well-versed in company processes or one who holds data essential for decision-making can wield power simply by being the gatekeeper of that information.

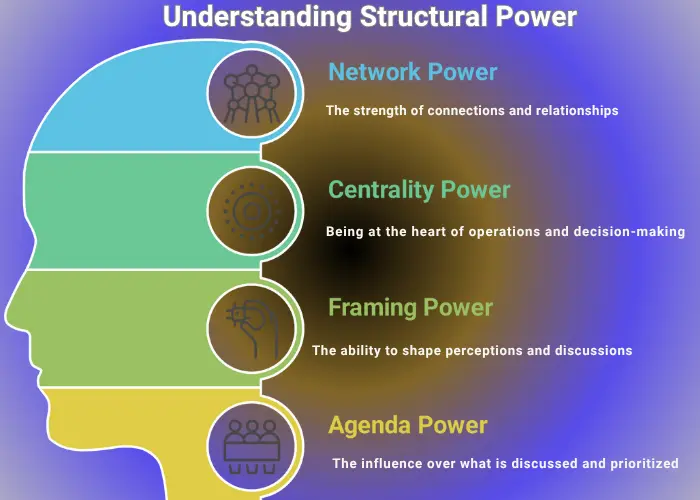

Structural Power: The Power of Placement

Structural power is all about where you are situated within the organization, both physically and within the network. The power you can exert is influenced by your position in the overall structure, your connections, and your visibility within the organization. Here are four key types of structural power:

Network Power:

- The strength of your network can give you power. The broader and more diverse your connections, the more you can leverage them. Network power is all about relationships—being well-connected can open doors and provide you with resources, information, and influence that others may not have. For example, someone with a large network of influential colleagues across departments can rally support for initiatives that they believe in.

Centrality Power:

- Centrality power comes from being at the heart of the organization’s operations. People who are in the loop—either because they are physically located near decision-makers or because they are involved in high-priority projects—are positioned to wield power. The more critical the role, the more centrality power a person can have. Being in the “center” of communications, decision-making, or operations means you control the flow of information and the decisions that shape the organization’s direction.

Framing Power:

- Framing power is the ability to shape how issues or situations are perceived. If you can control how a problem or opportunity is framed—for instance, defining a potential layoff as a “restructuring opportunity”—you can influence how people respond to it. Skilled communicators use framing power to guide discussions and steer the focus in the direction they prefer, making it an essential tool for leaders and managers.

Agenda Power:

- This is the ability to determine what gets discussed, prioritized, and acted upon. Those who control the agenda—whether it’s the topics of meetings, the issues addressed by the board, or the priorities of the department—have significant influence. In practical terms, an executive assistant who determines the schedule for leadership meetings or a project manager who decides the order of tasks can wield substantial power over what matters most.

Understanding Power Dynamics and Organizational Politics

Power within an organization doesn’t operate in a vacuum. The way it is wielded often intersects with organizational politics, a term that carries both positive and negative connotations. It’s important to understand how power dynamics play out in real-world scenarios—this understanding allows you to navigate the complexities of influence and leverage power more strategically.

The Reality of Organizational Politics

Organizational politics often gets a bad rap. However, when viewed through a more neutral lens, politics is simply the strategic use of influence to achieve non-sanctioned goals. In other words, it’s the art of navigating the unofficial, often unseen channels within the organization to get things done. This could involve gaining support for a project outside of formal approval processes or subtly influencing decisions to align with your priorities.

While political maneuvering can be seen as manipulative when used unethically, in many cases, it’s simply a means to drive results in environments where formal structures don’t always align with what’s best for the organization or its members. Effective political players understand how to read situations, build alliances, and use influence in ways that aren’t immediately obvious but still lead to positive outcomes.

At its core, organizational politics is about strategic relationships and timing. It’s not always about power struggles—it’s about finding ways to move forward and align your interests with the broader goals of the organization.

The Power of Social Networks

Your social network within the organization often reveals the “power that is,” rather than the “power that should be.” This means that, despite titles and hierarchical structures, the people with the most power are often those who are best connected within the informal networks of the organization. These are the individuals who know who to talk to, where to find resources, and how to influence decisions through relationships rather than formal authority.

For example, a senior executive might hold legitimate power, but if they aren’t plugged into the social network, they may struggle to mobilize action as effectively as someone with a broader, more connected network. Building relationships, establishing trust, and actively engaging with a range of people in your organization can be just as powerful as holding a high-ranking title. In many cases, the most influential individuals are not always those at the top—they’re the ones who can influence others across the organization through their relationships.

The 9 Organizational Influence Tactics: Mastering Strategic Action

Understanding power dynamics is important, but knowing how to wield that power effectively is what separates good leaders from great ones. This is where influence tactics come in. Influence tactics are deliberate strategies used to change the attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors of others, and they can be broadly categorized into soft tactics (for gaining commitment) and hard tactics (for ensuring compliance).

Soft Tactics (For Commitment)

Soft tactics are typically used when you want to gain commitment from others, not just compliance. These tactics appeal to people’s rationality, emotions, or values, often fostering a sense of shared purpose or mutual respect. Here are some of the most commonly used soft tactics:

Rational Persuasion:

- This involves using logical arguments and factual evidence to convince others to agree with your position or support your proposal. It’s about making a compelling case that’s backed by data, research, or experience.

Inspirational Appeals:

- This tactic uses emotion and values to rally support. You might appeal to people’s personal values or aspirations to inspire them to act in a certain way. For example, a leader might use an inspiring message about the organization’s future to motivate employees.

Consultation:

- Involving others in the decision-making process makes them more likely to support your ideas because they have a stake in the outcome. Consultation works because it makes people feel included, valued, and heard.

Ingratiation:

- This is about using flattery or friendly gestures to gain favor. While it’s not the most ethical form of influence, when used sparingly and authentically, it can help smooth relationships and create goodwill.

Personal Appeals:

- This tactic relies on personal relationships and emotions. It involves asking for something based on your relationship with the person, such as “I’ve helped you out before, and now I need your help.”

Exchange:

- This tactic is about offering something in return for support. It’s the concept of give-and-take—for example, “If you support this initiative, I’ll help you with yours.”

Hard Tactics (For Compliance)

Hard tactics, on the other hand, are used when you need to ensure compliance with a request or decision, especially when the individual may not be fully on board. These tactics can be more forceful or directive but are effective when there is no room for negotiation. Here are the most common hard tactics:

Legitimating:

- This tactic involves invoking formal authority or rules to justify a decision. For example, a manager might say, “This is the company policy” or “This decision was approved by the board.” It’s about leveraging the legitimacy of authority to secure compliance.

Pressure:

- Sometimes, when soft tactics aren’t enough, pressure is used. This could involve repeated requests, demands, or even threats of negative consequences if the request isn’t met. It’s a more coercive tactic that forces compliance, but it can also create resentment if overused.

Coalition:

- In this tactic, you seek to gain support from others to apply collective pressure on the individual to comply. By building a coalition of like-minded people, you can increase your influence and create a sense of solidarity that pressures the person to align with your goals.

Expert Insights: Common Mistakes and Advanced Power Use

Understanding how power is wielded in organizations is one thing, but mastering it requires a deep awareness of its potential pitfalls. In this section, we’ll discuss some of the common mistakes leaders and employees make when using power, explore the ethical considerations surrounding power use, and highlight the importance of cultural competence.

Common Mistake to Avoid: Hoarding Expert Power

One of the most significant mistakes leaders or employees can make is hoarding expert power. Expert power comes from possessing specialized knowledge or skills that others in the organization rely on. However, if you cling too tightly to this power—by refusing to share your knowledge or help others learn—you risk becoming a bottleneck in your organization’s growth and development.

Here’s the catch: while expert power can elevate your influence, training others or delegating knowledge can shrink your specific power, as others begin to acquire the same skills. But this is where the caveat comes in: upskilling is the key to maintaining your expert power. By constantly learning and improving your skills, you ensure that you remain the go-to person for the next level of knowledge or technology, thereby continuously renewing your power.

This principle is directly tied to the concept of transferable skills. As you share your expertise and develop others, you also have the opportunity to build your own transferable skill checklist—the ongoing process of learning and developing skills that can be applied to various roles within or outside the organization.

The Misuse of Power (Data Insight)

Power is a potent tool, but when misused, it can be destructive. Research conducted by the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL) reveals that 28% of leaders misuse power in ways that harm their teams and organizations. This misuse often occurs when leaders rely too heavily on coercive power or fail to consider the ethical implications of their actions.

The CCL study found that manipulation, bullying, and unethical decision-making are common ways that power is misused, leading to low morale, resentment, and ultimately a lack of trust within the team. These negative consequences undermine the effectiveness of a leader and create a toxic culture that can impact the entire organization.

To avoid the misuse of power, it’s essential to strike a balance between assertive leadership and ethical responsibility. Recognizing the impact of your decisions on others—and taking responsibility for the consequences—can prevent the harmful misuse of power.

Cultural Competence: What is Power Distance in Organization?

Understanding the cultural dimensions of power is vital for effective leadership, especially in global organizations. One critical concept is power distance, a term coined by social psychologist Geert Hofstede. Power distance refers to the extent to which less powerful members of an organization expect and accept that power is distributed unequally.

In high power distance cultures, hierarchy is accepted and respected, and leaders are expected to make decisions without much input from lower levels. In contrast, low power distance cultures tend to value more egalitarian structures, where decision-making is decentralized, and subordinates are encouraged to share their opinions.

Leaders need to recognize and adapt to these cultural differences in order to manage effectively across various environments. What works in one country or organizational culture may not work in another. For example, a directive leadership style may be well-received in a high power distance culture but could create resistance in a low power distance culture, where employees expect a more collaborative approach.

From Power to Empowerment: The Ethical Framework

The ultimate goal of power in an organization is not just to control but to empower others. True leadership is about uplifting those around you, enabling them to grow, and sharing the power you hold. In this section, we’ll explore how you can use your power ethically to foster empowerment and create a positive organizational culture.

Leadership is not about power over people, but power with people — the kind that turns influence into impact.Frances Hesselbein, Former CEO, Girl Scouts of the USA & Leadership Expert

Striving for Unity, Not Uniformity

One of the most powerful ways to empower others is through the embrace of diversity and inclusion. When organizations prioritize diversity—in all its forms, whether related to race, gender, background, or thought—they create greater collective strength.

By valuing diversity, organizations can draw on a wider range of perspectives, experiences, and skills. This diversity enhances innovation, improves decision-making, and increases organizational power. Unity, however, is the key. It’s about bringing diverse perspectives together and creating an inclusive culture where everyone feels valued, heard, and empowered. This unity fosters collaboration, ensuring that the organization is more adaptable, resourceful, and ultimately more powerful in achieving its goals.

Ethically, it’s essential for leaders to create an environment where differences are respected, and individuals have equal opportunities to contribute to the organization’s success. Emphasizing unity over uniformity ensures that power is used to elevate the collective good, rather than suppress individual voices.

Strategies for Preventing Abuse: Focusing on Transparency, Accountability, and Reliance on Earned Power

The risk of power abuse is real, but there are several strategies organizations can implement to prevent it. Transparency, accountability, and reliance on earned power (such as Expert Power or Referent Power) are essential for ensuring ethical power use.

Transparency

- Ensures that decisions are made openly and that the reasoning behind those decisions is clear to all. When leaders are transparent, they reduce the likelihood of unethical power plays because the rationale for decisions is out in the open for scrutiny.

Accountability

- Involves holding individuals at all levels accountable for their actions, particularly those with significant power. Leaders who model accountability ensure that their power is not abused, and they set the tone for the rest of the organization.

Reliance on Earned Power (like Expert Power or Referent Power)

- Instead of positional power ensures that influence comes from trust, respect, and competence. Leaders who build earned power lead with integrity, and their authority is rooted in their knowledge and relationships, not just their title.

Mastering Your Power in the Organization

In conclusion, Expert Power stands out as the most crucial, sustainable, and accessible source of influence within any organization. While titles and formal roles can grant you positional power, it’s your expertise—the unique knowledge, skills, and abilities that others rely on—that provides lasting impact and respect. Expert power is not only within your control but is also adaptable and expandable as you continue to learn, grow, and share your knowledge with others.

Regardless of your rank, Expert Power allows you to build relationships, earn respect, and lead with influence. It’s the power that transcends job titles, and its value increases as you invest in continuous improvement and share your expertise with others. This type of power is inherently democratic—available to everyone who seeks to improve and contribute meaningfully to their organization.

Clear, Actionable Call-to-Action:

Now that you have a deeper understanding of the sources of power and how to wield it ethically, the next step is to take action. Start by assessing where you currently stand in terms of your own power sources, particularly your Expert Power. Do you have a skill set that is in high demand? Are there areas where you can increase your expertise or share your knowledge more effectively?

Build your Transferable Skill Checklist today. This checklist should include:

- Core Skills: Identify the skills that give you leverage in your organization.

- Learning Goals: Determine areas for improvement and focus on acquiring new knowledge that will increase your value.

- Actionable Steps: Break down your learning goals into smaller, actionable steps that you can implement daily.

By consistently working on your Transferable Skills, you can systematically increase your most valuable source of power, positioning yourself as an indispensable asset to your team, and ultimately, an influential leader in your organization. The process of continuously upskilling is your pathway to maintaining and expanding your Expert Power, ensuring you have the influence you need, regardless of your position.

Take charge of your growth now, and begin building a future where your power is both earned and ethical, ensuring long-term success and satisfaction within your organization.

Power Decoded: Answering Your Top Questions on Influence, Dynamics, and Politics in Organizations

Power distance refers to how much inequality in power is accepted in an organization’s culture, per Hofstede’s model. High distance means hierarchical deference (e.g., in traditional firms); low fosters equality and open feedback, impacting motivation and innovation.

Power dynamics describe how influence shifts among individuals/groups in organizations, influenced by hierarchy, networks, and conflicts. Positive dynamics build collaboration; negative lead to silos or toxicity, often seen in team negotiations or remote setups.

Ethical power tactics, like rational persuasion or coalition-building, involve logic and alliances to influence without manipulation. In OB, they foster trust and reduce resistance—e.g., a manager using inspiration to align teams on goals, avoiding coercion’s backlash.

In management, power enables directing resources, decisions, and teams toward goals. It balances authority (e.g., setting policies) with influence (e.g., motivating staff), ensuring efficiency while preventing abuse through transparent communication and empowerment.

Power fuels organizational politics—the informal influence games for resources or status. In OB, positive politics build alliances for change; negative breeds favoritism. Leaders navigate by promoting transparency to align politics with org goals.

Yes, through personal power like expertise or networks. Entry-level staff can gain influence by sharing knowledge (expert power) or building relationships (referent), as in remote teams where visibility via contributions trumps hierarchy.

Power misuse, like excessive coercion, erodes trust, boosts turnover (up to 50% per Gallup), and stifles innovation. It creates toxic cultures, leading to legal risks or low morale—countered by accountability policies and ethical training.

Cultural diversity influences power via varying acceptance of hierarchy (high power distance in collectivist cultures). It enriches dynamics by blending perspectives but requires inclusive tactics to avoid biases, enhancing creativity in global teams.

Remote work flattens hierarchies, shifting power to informational/expert sources (e.g., via digital tools). It reduces coercive control but amplifies network power through virtual alliances, demanding clear communication to prevent isolation or unequal influence.

Use surveys on perceived influence (e.g., power distance indexes) or network analysis tools. Balance via rotations, training, and DEI audits to prevent imbalances, ensuring equitable dynamics that boost engagement and performance.

- Be Respectful

- Stay Relevant

- Stay Positive

- True Feedback

- Encourage Discussion

- Avoid Spamming

- No Fake News

- Don't Copy-Paste

- No Personal Attacks

- Be Respectful

- Stay Relevant

- Stay Positive

- True Feedback

- Encourage Discussion

- Avoid Spamming

- No Fake News

- Don't Copy-Paste

- No Personal Attacks